Eclipse

Symphonic Band

Composed for the International Project at Perugia Conservatory, Umbria, Italy

Full ScoreReturn to the Mean Streets

Any number of instruments or singers

Composed for the Carroll University Wind Symphony.

Instructions Parts in C Parts in B flat Parts in E flat Parts in FSnapper

Networked laptop ensemble

Composed for CLIME for the Catalyst Project at Carroll University.

Tectonic Shift

Live interactive audio and video installation

Installed at the STUDIO 300 Digital Art and Music Festival, Transylvania University, Lexington KY

Detour

Cello ensemble and piano

Commissioned by the Advanced Cello Ensemble (ACE) at the String Academy of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

ScoreRosalind's Revenge

Solo percussion

Composed for Jude Traxler for Classical Revolution Cincinnati

ScoreTilting

Prepared MIDI piano, laptop, Arduino, and 3 pinwheels

"You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows." - Bob Dylan

Circuit Drawing #2 (with Paul Schuette)

Electronic Installation

This circuit drawing, installed at the Emery Theatre in Cincinnati, was a collaborative effort with artist Paul Schuette. As a play on the conventions of a box office, the user interface for this piece is a magnetic card swiper.

The Listening Box

Live uncontrolled solo laptop

The music we make is intimately tied to our bodies. Rhythm is an expression of our pulse; phrases are born of our breath. But a computer has neither heart nor lungs. What kind of music would it choose to make?

All of the sounds in this piece are generated live by the computer, without input or control from a human operator. There are no predetermined rhythms, or pitches, or timbres. The computer listens to its own body, through contact microphones on its case. The input sound is analyzed, filtered, and arranged into gestures according to timbral and dynamic similarities.

Strike

MIDI piano, tam-tam, laptop

When I studied photography and darkroom techniques several years ago, I found that my best photos involved examining the intimate details of familiar objects, framing them tightly and removing context. I try to apply a similar technique to my music.

“Strike” explores a simple repetitive chiming texture, but I fracture the music into its atomic units: pitch, duration, repetition tempo, and onset time. These develop at different rates throughout the piece, tracing long sine waves at different frequencies. Dyads flow up and down the piano, their sinuous path only occasionally audible as the tempo traces its own peaks and troughs.

The tam-tam itself is never struck but, from its position directly in front of the piano, resonates sympathetically with the sound reaching it. This vibration is amplified by a piezo contact microphone.

Physica

SSAA and live electronics

1. The Nightingale

2. The Mole

3. The Unicorn

Hildegard of Bingen is best known for her mystical visions, but she was also a composer, physician, and scientist. Her text Physica describes the natural world through the peculiar lens of medieval thought. She ennobles the lowly mole, endowing it with "a great internal knowledge," while attributing the nightingale's gallbladder with the ability to cure blindness. Her detailed instructions on how to catch unicorns is curious and unsettling. Hildegard's words are placed in counterpoint with the words of the fourteenth century English mystic Julian of Norwich, who describes her miraculous healing and a vision of the world as a hazelnut; and contemporary American poet Kathleen Norris's "In Praise of Darkness," a meditation on spirituality and nature. The texts are intertwined, drawing connections between words written centuries apart.

Each movement is centered around a different electronic synthesis technique, revealing the Hildegard text to the choir as a mystical voice.

Physica was premiered on 24 March 2012 by Vox Musica in Sacramento, CA.

In the Mean Time

MIDI piano and live electronics

Two systems in competition, each with a distinct relationship to pitch and rhythm.

The first, a MIDI-controlled piano piece which incorporates a variety of rhythmic schemes: ostinato, indeterminate rhythms, tremolo, trills.

The second, a computer running an interpolating variable delay line based on a moving average of rhythms it hears. (The mean time, get it?) The computer tries to determine the current tempo and replay what it hears, several beats later. A steady rhythm by the piano results in a simple canon. But changes in the piano rhythm lead to changes in the average tempo. And as the delay time changes, the pitch also changes. An accelerando leads to an upward shift in pitch; a tremolo results in a subtle (or not-so-subtle) detuning effect.

The moving average controlling the delay line works to smooth things out, but the piano continually tries to throw it back into chaos.

Terms of Venery

Baritone voice, marimba, percussion

Collective nouns, the varied and whimsical names given to groups of animals (and occasionally people) are a unique feature of the English language, and they have a venerable lineage. They arose as a way to distinguish aristocrats who were well-versed in the language of hunting. (Only an educated hunter would know that a group of geese is called a gaggle when it is swimming, but a skein in flight.) Some of these terms remain exotic to us—a covey of quail, a sounder of boar—but others have become so commonplace that we seldom consider how odd their origins. A pride of lions, a school of fish, a litter of puppies. Pride? School? Litter!? Only when these terms are de-coupled from their partners do we see how strange and poetic our language is, and to what lengths we will go to describe the world around us.

Score NotesPeepums

Accordion and multiple networked laptops

Peepums is like a high-speed game of telephone, in which a word or phrase is passed around a group, transforming as it goes. Here the laptop computers are passing the word among one another, and the human operators only get to decide whose “words” to listen to, and how to interpret that information in sound.

Of course, the computers are sharing not words but data. The cycle begins with a single piece of information: a pitch played on the accordion. The computer tracks the pitch as a MIDI note number (where 60 equals middle C) and passes that number wirelessly to the next player in the chain, who plays the pitch on his or her laptop, then passes it on the next player, who in turn plays the pitch and passes it on...

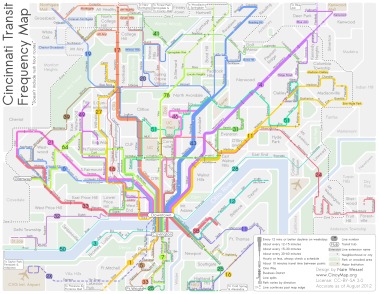

As the piece progresses, the players alter the flow of data, transforming the pitch and rhythm, and grabbing information from multiple other players, creating short-circuits, whorls, and drones. The visual projection shows the pattern of connections and the rise and fall of pitches within the ensemble.

Peepums was written for CiCLOP, the Cincinnati Composers Laptop Orchestra Project.

Shear Pin

2-channel fixed format

The hay baler was the most interesting machine on our farm. It had hundreds of moving parts—gears, tines, knives—all rotating at different rates, but intricately coordinated, powered by a single flywheel.

The shear pin was a safety bolt designed to break—to shear off—when the machinery malfunctioned, causing the flywheel to spin madly fast, harmless, while everything else ground down with a dreadful ticking noise. I remember one occasion in which the cause of the problem was a mystery, and I had to clean the hay out of the main chamber and crawl through it to track down the offending part that had thrown the machine out of balance. The baler was old, greasy, rusted, but years of operation had polished the steel walls mirror-smooth, and the bolt heads were worn round like pebbles in a stream. In this strange intimate place, the baler seemed to possess a will of its own, and I imagined the machine adjusting itself, seeking a state of balance.

In this sound machine, the flywheel is an unchanging, very fast metapulse, from which all of the various tempi and tuplets are derived. The machine approaches the listener, its various processes coordinated. It attempts to shift itself into a high gear, but the strain causes the pin to shear, wrecking the pulse and disturbing the balance. Gradually the machine rights itself, gathers momentum and continues on its way.